Formal Accommodations: Disability and Political Economy in Romantic Literature

My first book project makes two important interventions: first, it rethinks the Romantic period in terms of the history of disability, and second, the history of disability in terms of the critique of political economy. Although the Romantic period is not typically understood in relation to disability (a category of identity that emerged in the twentieth century with the advent of the disability rights movement), I argue that the period needs to be reframed in this way because it witnessed the rise of the welfare state and the establishment of state provisions for the “impotent” (i.e., disabled) poor. At the same time, I reframe disability in Marxist terms as a corrective to “social models” that identify its origins primarily in infrastructural and attitudinal barriers to accessibility, rather than the social relations of production. Beyond these acts of historical re-description, I argue that British Romantic literature imagines the disabled body as a figure for the production and expenditure of value. Drawing on a wide array of authors, including Sarah Scott, Priscilla Pointon, William Wordsworth, Jane Austen, Lord Byron, Harriet Martineau, and Robert Blincoe, I use literary form to introduce a reading practice that bridges aesthetics and an account of disability’s imbrication with capital.

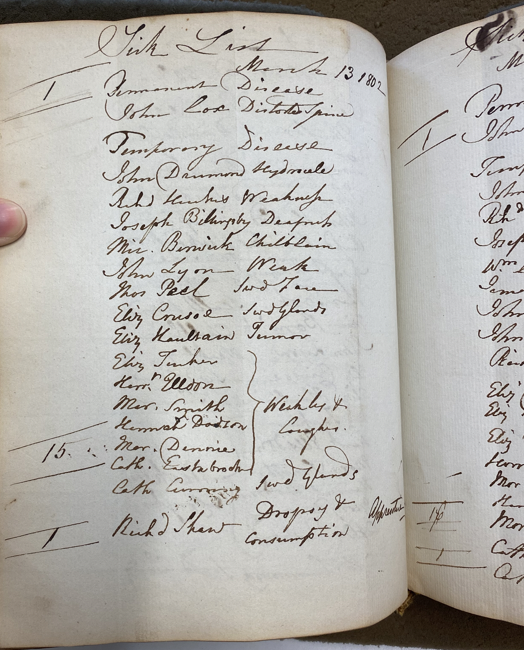

ID: A page from an open book features the words “Sick List” and “March 13, 1802” in cursive. It lists Foundling Hospital residents, with their names handwritten in a left-hand column and their corresponding “disease” identified in the right-hand column. Courtesy of London Metropolitan Archives (A/FH/A18/5/7).

Canary Knowledge: Chronic Fatigue, Chemical Sensitivities, and the Limits of Medicine

I co-organized a two-day symposium celebrating the publication of the Oral Histories of Environmental Illness (OHEI) archive at UCLA’s Young Research Library, a collection of interviews with 80+ individuals living in the U.S. and Canada who either identify as having an “environmental illness” and/or treat and advocate on behalf of those with “contested illnesses” (e.g., multiple chemical sensitivity, chronic Lyme, and mold-related fibromyalgia). The interviews were collected from 2018 to 2021 by a team of faculty, graduate and undergraduate students, and staff researchers at the UCLA Center for the Study of Women.

The event kicked off Year One of a major multi-campus research grant at the University of California focusing on “Abolition Medicine and Disability Justice: Mapping Inequity and Renewing the Social.”

With Rachel C. Lee and Abraham Encinas, I have co-authored an article based on the OHEI archive, titled “‘Settler Maintenance’ and Migrant Domestic Worker Ecologies of Care,” for “Care in the Environmental Humanities,” a special issue of Humanities edited by Alice Hall and Thomas Houlton.

Abstract: Oral histories of Latina domestic workers in the United States feature hybrid narratives combining accounts of illness and “toxic discourse.” We approach domestic workers’ illnesses and disabilities in a capacious, extra-medical context that registers multiple axes of precarity (economic, racial, and migratory). We are naming this context “settler maintenance.” Riffing on the specific and general valences of “maintenance” (i.e., as a synonym for cleaning work, and as a term for the practices and ideologies involved in a structure's upkeep), this term has multiple meanings. First, it describes U.S. domestic workers’ often compulsory use of hazardous chemical agents that promise to remove dirt speedily yet imperil domestic workers’ health. The use of these chemicals perpetuates two other, more abstract kinds of settler maintenance: (1) the continuation of socioeconomic hierarchies between immigrant domestic workers and settler employers, and (2) the continuation of (white) settlers’ extractive relationship to the land qua private property. To challenge this logic of settler maintenance, which is predicated on a lack of care for care-workers, Latina domestic workers have developed alternative forms of care via lateral networks and political activism.

ID: The symposium’s flyer features dark purple text set against a light purple, ink background.

ID: A pair of headphones rests on a book, in an image taken from the UCLA Center for Oral History Research’s website.